A Child’s Memory Of WW2 by David Ford 2005

‘Three lights and a bung’

I was born and was living in Hall Street, Long Melford when World War 2 began. At the age of five I was too young to realise the seriousness of what was going on, but certain things, which eventually turned out to be of such importance, are held on a floppy disc in my inbuilt memory. In Long Melford we had no sewage system and only a few houses in the village had electricity. A programme of wiring which became known in the trade as ‘Three lights and a Bung’ the Bung being a two pin 5 amp socket, the third pin the earth was thought not to be necessary. Now we understand more about electricity, the third pin ‘the earth’ in this ‘lectric thingy’ as my mother called it is the most important. We had gas lighting in two rooms of our house, which was “Far better for your eyes” as far as my mother was concerned, this must be right because she knew so much about so many things. We also had a battery operated wireless set run by a huge battery called a High Tension battery, another battery called a Grid Bias also an Accumulator wet battery which had to be taken to the local radio shop for recharging. I could never understand why it took so long to charge a battery; surely the charge came in a packet… all they had to do was to tip it in. When I left school I worked for an electrical firm, it was then everything fell into place.

She could coddle a meal out of thin air

When much later in life I managed to get my mother to talk about her life I discovered she had left school in 1917 at the age of ten to help look after the house and family whilst her mother went out to work to pay the rent and feed the family, many times my mother told me they had virtually nothing to eat, quite often neighbours would leave rooks and sparrows on the doorstep which my mother would make into a pie or more often a stew, with vegetables when in season from the garden. My mother’s father had been killed in a farm accident at the age of 35, in 1911 leaving a widow and five children, all the eventual hard way of life stood her in good stead for feeding us during the forthcoming war, we never went hungry, she could coddle a meal out of thin air and have plenty left over for the next day, though quite often we never knew what we were eating or cared, it was food.

“We could all hev bin killed jist as bloody easy walking down the strit”

My first collection of the war was waking up in the cellar of our home, seeing through the dim light of a candle standing in the old enamel candlestick holder, which was used when going to the bucket toilet at the bottom of the yard at night, I could see in this dim light my uncles and aunts and my grandmother sitting on wooden boxes and the stairway of the cellar. A few months later I seemed to be more conscious of what was happening and realised why all my family had walked down the street to seek refuge in our cellar when the air raid siren sounded for the first time in Sudbury, our only form of warning. They repeated this visit to our cellar on a couple of occasions until my uncle George quipped, “We could all hev bin killed jist as bloody easy walking down the strit”. They never came again. After those first few visits to our cellar I soon realised there was something serious going on. I had heard tales from my seniors about the First World War, and I always admired my grandfather who had served with the Suffolk regiment. I have often wondered what must have gone through my parent and grandparents minds, they had lived through a ‘War to end all Wars’ and were now facing another. They had also lived through a worldwide financial depression and a general strike.

My personal memories of my grandparents are few but they linger because there was so much going on in everyone’s life at that time with the war and my memory of early years relates everything to that period, new life and death along with illness still carried on, war could not stop nature. Although we lived next door to a sweet shop we were rationed and there was also a limited variety of sweets to purchase providing we had the money and sufficient coupons.

Our lives changed completely after the first night spent in the cellar. Life was exciting yet terrifying, we all were fitted with gas masks, mine an ordinary black one, my sisters an incubator style and then she progressed to a ‘Mickey Mouse’ style.

Melford…saw change overnight

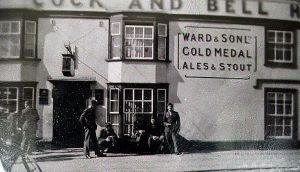

Up until WW2 started I had always been safe running across the road to my grandmother’s house or going to the butchers shop with an envelope containing a ten shilling note and stating what joint my mother required, enough to last for three days’ meals and a sandwich for my dad’s work lunch. Today the same joint would be almost out of the financial reach of a lot of people. Melford, being situated on the main road between two garrison towns, Colchester and Bury St Edmunds, saw change overnight, it was no longer safe for young children to cross the road alone. There were military vehicles, dispatch riders and tanks along with the familiar sight of horses pulling farm carts. There were also Squads of soldiers being drilled up and down the road, but even they had to give way occasionally to animals being driven to market in Sudbury or to a change of pasture.

Any empty building was taken over by the army for billets, and also military bands used to make lovely sounds rehearsing for the Sunday Church Parades.

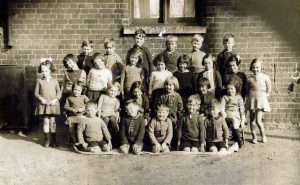

Due to teachers being called into the RAF our education suffered dramatically. We had very basic teaching often being herded into two adjoining classrooms with the headmaster standing between the rooms defying anyone to talk and making sure they did the work on the blackboard.

The Military had taken over both Melford and Kentwell Hall. The Hyde Parker family, residents of Melford Hall moved out and lived in a large house overlooking the green, the Army moved in and almost destroyed it by fire. Mr and Mrs Starkie Bence, residents of Kentwell Hall moved into one wing of the hall and the Army took over the rest. The hall at Liston, just outside the village of Melford, was also taken over by the military and later became the base for Italian prisoners of war.

Searchlights, tank traps, slit trenches…roadblocks

In and around the village there were searchlights, tank traps, slit trenches dug in strategic places, roadblocks and gun emplacements which were lumps of concrete with stainless steel Spigots protruding from the top capped over with a tin of grease. This grease caused my clothes and my boots to get in a state and nearly all the family’s clothing coupons went on boots for me.

As children we were now playing fighting the Germans instead of cowboys and Indians. Our friends the soldiers gave us hands full of live 303 rifle bullets which we pulled apart, retrieving the cordite explosive making a pile and then applying a lighted match, making quite a good display with a few bullets. The greatest fun was to put a bullet in a vice and then with a nail and hammer strike the detonator and fire the bullet, how some of us survived the war I shall never know, we shot so many bullets like this that we made quite a large hole in the end of the shed.

We were warned not to pick up any suspicious looking objects. There was one occasion when some boys found an unexploded bomb and dug it up and laid it on the headmaster’s lawn. The military were called and they removed the bomb to Melford Hall Park where they made a controlled explosion. We were spontaneously given a day off school as we were when it was used as a resting place for the evacuees.

I have clear memories of the evacuee families in particular the family of a London Policeman. There was a mother with a five year old skinny little daughter who was always skipping everywhere, a four year old son and they stayed in a rat & mouse infested house with a water pump one hundred yards up the road. Another baby was born to this family and the two older children stayed with the teacher and his wife while the mother was in hospital having the baby. The two families became firm friends. I remember, after I had finished my National Service in 1954, I attended a dance in the village and had the last waltz with the policeman’s daughter. I walked her home to the teacher’s house. In 1956 the policeman and his family retired to live in Melford and in 1957 I married the skinny little daughter.

Two American bases

As war progressed the two American bases opened with a satellite hospital at another large house in the area – Acton Place which also had a mortuary. Ambulances used to meet the ambulance train at Melford railway station and drive through the village to the hospital at Acton.

As children we witnessed some horrific incidents, one I remember was watching a plane spinning and diving earthward and closing on the ground at a terrific speed and not pulling out of the dive, there was a horrific explosion and a gigantic ball of flame and smoke. There was no descending parachute and I went home feeling very sick in the stomach and realising that war did not have that same appeal.

There was worse to come. My mates and I witnessed many horrific incidents. One which stuck in my mind more than anything is of a pilot hanging on the end of his unopened parachute with his legs kicking in mid-air and his arms pulling frantically at the rip cord. I did not see what happened to him but did hear of his fate later.

One day we helped to rescue an aircraft crew member who was dangling from the end of his parachute which was entangled in a tree. I stayed with him whilst my mate ran to find help. He found a jeep loaded with American soldiers who didn’t know what to do. Fortunately some British Squaddies climbed the tree and lowered the airman to the ground by his parachute.

As the war progressed I delivered telegrams for the local Post Mistress. These yellow envelopes did not always carry good news. Some would read, ‘Regret to inform you, your son/husband is missing, presumed dead’. This would be followed up by a handwritten letter from the deceased’s commanding officer. One of my aunts received these a few weeks after D Day. I did not comprehend the heartbreak she must have felt, to me my uncle was a hero of whom I could boast about at school.

My bedroom overlooked Hall Street, the main street through Melford, and I witnessed many sights including fights between the black and white Americans. Some were quite horrific, in hindsight these were very racist.

It was ‘D’ Day

One morning I was awoken quite early by a lot of noise in the street and saw the roads and pavements packed solid with military vehicles of all shapes and sizes all going the same way. We later learned that it was like this all the way to Harwich, it was ‘D’ Day. From then on Melford became a much quieter place and the war seemed to come to an end very quickly.

The American Hospital at Acton became a POW camp for Germans. The camp also held Displaced Persons known as DP’s from Eastern Europe. I was by this time helping my future employer during my holidays and helped to carry out some electrical work in the huts where the DP’s were living. We treated each other with a little suspicion, we could not understand each other and they cooked strange smelling food, not the meat and two veg I was used to. Eventually we broke the ice with smiles of greeting. As we were rewiring the kitchen the cook offered us some food which I declined but the resident site engineer tasted it and enjoyed it. I think they were Hungarians, so the dish could now be on our supermarket shelves.

When the DP’s left the huts they were then occupied by English squatters, they were mostly ex-servicemen who had married Melford girls and were living in overcrowded conditions with their In-laws. My firm was contracted to rewire the lights and one 5 amp socket. The huts were in use for quite some time until a programme of building new council houses was well underway. The squatters were first to be re-housed in the many council houses which later sprung up around the village. One of my mother’s sisters was amongst the first group to squat, much to my mother’s annoyance. “Common old lot, I don’t know what you want to have anything to do with them for, that’ll git you into trouble, you mind my words”.

This time for once she was wrong.

© Copyright of content contributed to this Archive rests with the author – David Ford.*

*A Child’s Memory Of WW2

Childhood and Evacuation – Contributed by Action Desk, BBC Radio Suffolk

People in story: David Ford, The Hyde Parker Family, Mr & Mrs Starkie Bence (Kentwell Hall)

Background to story: Civilian – Article ID: A4453373 – Contributed on: 14 July 2005

WW2 People’s War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar’